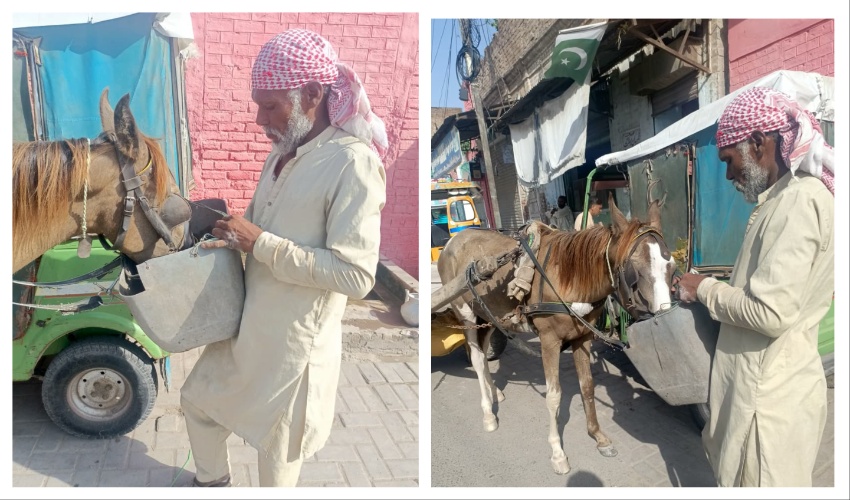

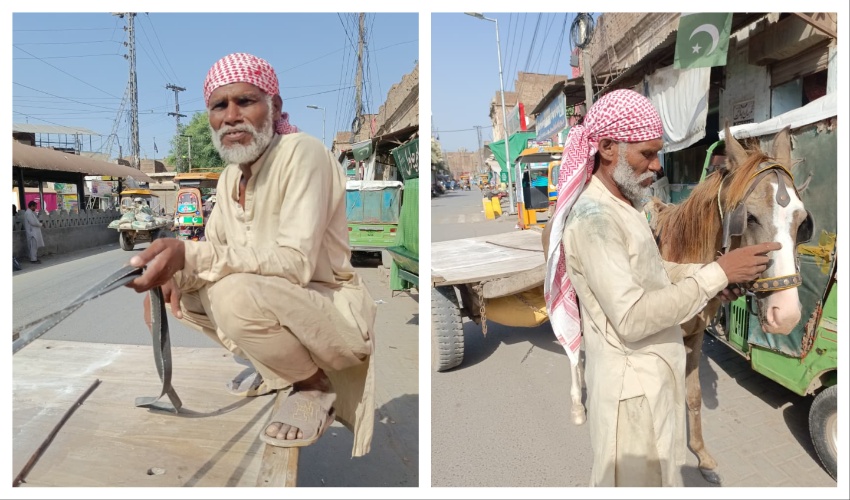

The sun over Jhang doesn’t just rise anymore, it swells, boiling the air before noon. On a cracked road outside the city, Mukhtar Ahmad, 60, wipes his face with a rag that’s already soaked through. His horse tugs faintly at the rope, its ribs showing.

“Last year,” he says, “I lost my other horse. He fell down in the street. The doctor said it was heatstroke.”

Mukhtar has pulled a cart for two decades, carrying bricks, grain sacks, and whatever the day demands. His fifteen-hour shift earns barely Rs 1,000–1,200 — enough to feed his wife and three daughters if the weather allows.

(Mukhtar shares a moment of kindness with the horse that keeps his livelihood moving—Picture credit: Wajid Ali)

(Mukhtar shares a moment of kindness with the horse that keeps his livelihood moving—Picture credit: Wajid Ali)

But when the heat hits 48 degrees, as it did this July, he stays home.

“If I go out, I could lose this one too,” he says, nodding at the animal. “If I stay home, my family goes hungry.”

He sighs, half-resigned, half-prayerful.

“Puttar, ay Allah da kam ae — it’s God’s will. What can we do?”

His words echo through Pakistan’s informal streets — where faith, fatigue, and a failing climate now meet.

The Pakistan Meteorological Department calls this the hottest decade since records began. In July 2025, Punjab baked at 48°C, while flash floods drowned entire neighbourhoods. In Jhang alone, over twenty deaths were reported after the Chenab burst its banks.

LAHORE — The woman who refuses to stop working

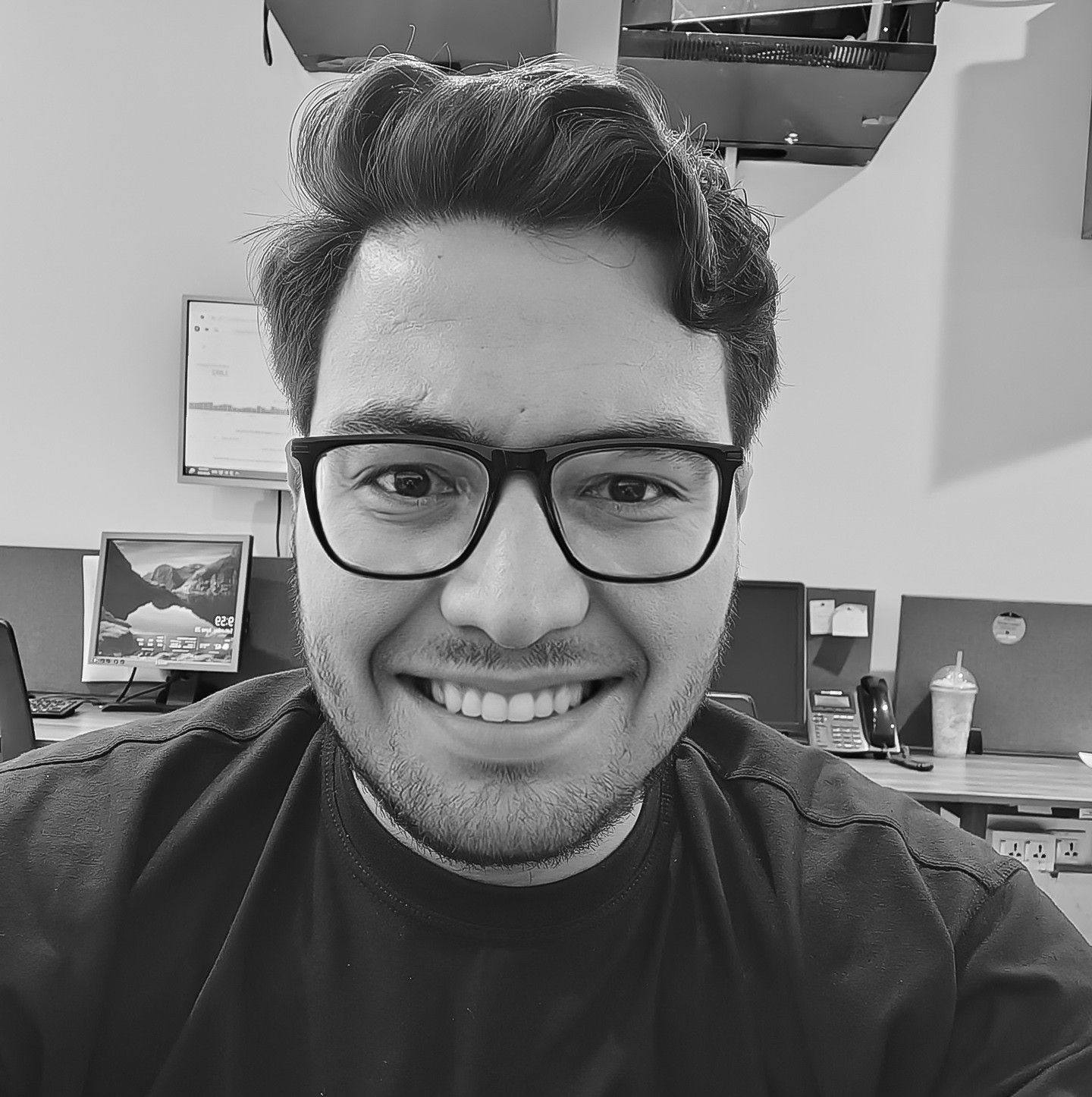

Three hundred kilometers away, in Lahore’s Liberty Market, between the stalls of branded shoes and glass storefronts sits Sakina Bibi, 58, her small bucket of hairpins and combs arranged neatly on the ground.

She’s been here for fifteen years, through smog, floods, and scorching summers.

“Everyone here knows me as Sakina Ama,” she says. “I sit here at one o’clock and leave at nine. This place feeds my children.”

In June, as the temperature crossed 44°C, she fainted under her umbrella.

(Sakina’s quiet resilience lights up Liberty Market, Lahore. - Picture credit: Wajid Ali)

“I thought I was dying. My head was spinning, my chest was tight. The doctors said it was heatstroke.”

After two days in the hospital, she was back — sitting again in the same spot.

When asked if anyone from the city administration visited, she laughs softly. “No one came. We do what we can. I keep a small cooler, some wet cloth, and water bottles.”

But her worry is not just the heat. It’s the air.

“Every winter, the smog turns this place into smoke. My eyes burn, I cough all night. But still, I must sit here. If I don’t sell, who will feed me?”

She pauses, then adds quietly,

“This is Allah’s test. He is showing us His power.”

BAJAUR - The cobbler who calls it the end of times

A few kilometres away, in Lahore’s Anarkali bazaar, Muhammad Haroon, 34, crouches beside his wooden box of brushes and shoe polish.

He came from Bajaur two years ago, sending most of his Rs 1,300 daily earnings to his parents and sister back home.“In Bajaur, summers were hot, but not like this,” he says. “Here, even at night, the road burns like a tandoor.”

Haroon works ten hours a day, but on the hottest afternoons, customers vanish.

(The above is a representative picture of Muhammad Haroon, who preferred not to be photographed - Picture credit: Google Gemini)

"People don’t come to polish shoes when their own soles are melting,” he jokes bitterly.

He has heard of climate change but sees it through the lens of faith.

“Brother, this is Allah’s wrath. The world is ending — these floods, this heat, this sickness. It’s written.”

Then, with a half-smile, he adds,

“We are sinners. Allah is just showing us what we did.”

FAISALABAD — Fruits, floods, and faith

On Faisalabad’s Canal Road, Shakir Ali, 52, pedals his cycle stacked with baskets of guavas and pears. He buys from the wholesale market at dawn and sells until sunset.

“I used to sell oranges in winter,” he says, “but now, every year, the crops are late or small. Rain doesn’t come when it should. Floods destroy the rest.”

He wipes his forehead and points to the grey air.

(This fruit cart belongs to Shakir Ali in Faisalabad, who preferred not to be photographed. — Picture credit: Wajid Ali)

“Smog makes people sick. They stay home. And fruit goes bad faster in this heat. Allah tests us in many ways.”

He too believes the disasters come from heaven. “We can’t fight His will,” he says. “The earth belongs to Him.”

A billion-rupee storm hitting invisible people

These four voices — different cities, same belief — form a portrait of Pakistan’s street economy, where faith has become a refuge, and sometimes, a replacement for climate literacy.

Each of them has lived through floods, heatwaves, and smog. Yet all four denied that these disasters are human-made.

For them, climate change is not the sum of industrial emissions or deforestation; it is the unfolding of God’s will.

They see the rising heat, the dying animals, the choking air — but not the factories behind it, the concrete that replaced trees, or the politics that allowed rivers to drown towns.

They are living through climate change — and yet, they don’t believe in it.

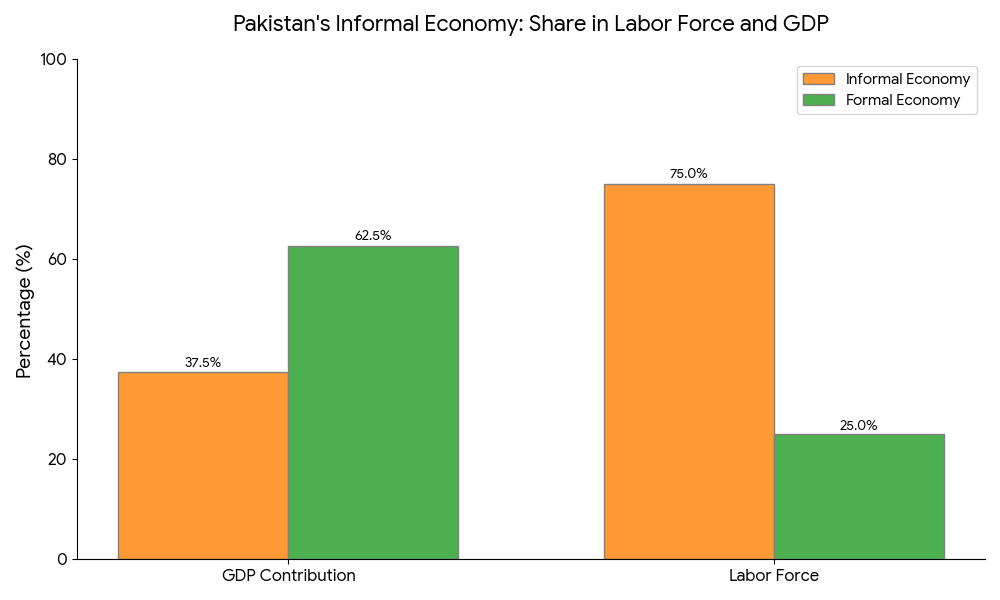

Beneath that faith is a staggering economic reality. Pakistan’s informal economy, often called the “shadow economy,” employs nearly three-quarters of the labour force — around 55 to 57 million people — most without formal contracts, insurance, or social protection.

It contributes roughly 35–40% of the country’s total GDP, valued at around $380 billion, according to estimates from the Pakistan Institute of Development Economics (PIDE) and the International Labour Organization (ILO).

Most of these workers are outdoor earners — vendors, cart pullers, masons, loaders, and transporters — exposed directly to the sun, dust, and monsoon rains.

When the 2025 floods struck, it wasn’t factories or offices that collapsed first — it was work like theirs.

And when the summer brought wet-bulb temperatures beyond 32°C, the threshold where even rest breaks can’t prevent heatstroke, these workers continued anyway — because hunger doesn’t wait for the weather, and belief doesn’t bend to science.

Their resilience is admirable. Their denial is tragic. And together, they reveal the hardest truth of Pakistan’s climate story: The poor are paying for a crisis they don’t believe they created — or can control.

“Allah’s Will — and the laws we keep breaking”

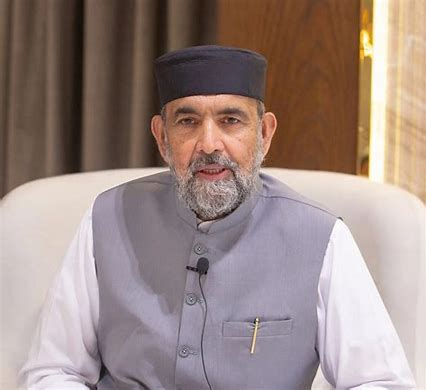

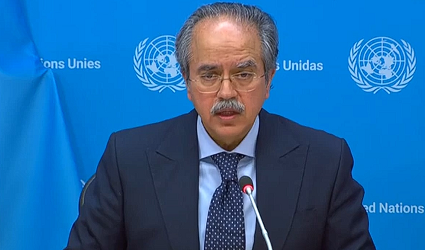

When asked why so many Pakistanis interpret climate change as divine will, Professor Qibla Ayaz, former Chairman of the Islamic Ideology Council, recited a verse:

“Allah says (85:16), ‘He does whatever He wills.’

But Allah also governs by principles. He will not feed a man who does not work.

Likewise, He will not protect a planet we keep destroying.”

(Prof. Dr. QIBLA AYAZ - Former chairman of Pakistan Council of Islamic Ideology)

He quoted Qur’an 30:41 —

‘Corruption has appeared on land and sea because of what people’s hands have earned.’

“This,” he said, “is the Quranic definition of climate change. We violated the mizan — the balance Allah created — and now we taste the result.”

Qibla Ayaz also blames not ignorance, but greed — a moral imbalance as much as an environmental one.

“The capitalist system has destroyed this balance.

Some countries withdrew from climate agreements, calling climate change a lie.

The rich chase profit, even if they burn the planet’s lungs.

This is not Allah’s will — it is our arrogance.”

Faith as climate governance

Ayaz argues that clerics must be integrated into national climate programs, not as token figures but as moral communicators.

“We saw it during the polio and COVID campaigns — when scholars spoke, people obeyed.

Let every mosque announce heat alerts, every Friday sermon talk about water, and every madrassa teach that cutting trees is a sin.”

He calls this “eco-Islam in practice.”

“The Prophet (PBUH) gave us the world’s first environmental charter — don’t waste water, don’t harm animals, don’t destroy greenery.

If we revived those teachings, our climate policy would have a conscience.”

God loves clean environment

For Professor Qibla Ayaz, climate justice is more than survival — it is a sacred duty. “Heaven,” he says, “is described in the Qur’an as gardens, rivers, shade, and pure air — which means Allah loves a clean and balanced world. A climate-friendly earth is not just sustainable; it is spiritual. If we wish for heaven, we must build a little of it here.”

And that vision demands action — not only from policymakers, but from every believer. Pakistan’s battle with climate change will not be won in conference halls; it will be fought on its streets — in the shade of Mukhtar’s horse, under Sakina’s umbrella, on Haroon’s burning pavement, and beside Shakir’s fruit cart rattling through smog.

The way forward, Ayaz insists, lies in uniting faith and policy. Mosques should become centers of awareness, announcing heat alerts and flood warnings. Friday sermons must preach stewardship alongside salvation, teaching that wasting water or cutting trees is as sinful as neglecting prayer.

Every school and madrassa should make environmental ethics part of its syllabus, showing children that planting a tree is an act of worship.

And the government, in turn, must recognize and protect the millions of informal workers — by providing shade, clean water, and health safety nets for those who keep the country’s economy alive. The urgency could not be clearer.

With La Niña expected to bring one of the harshest winters in years and smog already choking Punjab’s skies, Pakistan stands between survival and surrender. Climate change will not wait for belief to evolve — but belief can still become the catalyst for action.

The same verses that describe paradise — gardens, rivers, clean air — describe the world Allah entrusted to us. To protect it is not a policy; it is prayer in practice. And perhaps, when Pakistan rediscovers that divine ecology — when sermons, citizens, and statesmen move as one — the next season, whether of heat or haze, will bring not only hardship,

but also hope.