Global bodies are declaring Pakistan’s economy to be stable. The words “moderate growth” now dominate reports from multilateral lenders and organizations when describing the country’s economic health. However, it is unfortunate that this stagnation is being considered a success. The United Nations projects a 2.3 percent growth rate for Pakistan this year. The IMF is marginally more generous at 2.6 percent. However, neither number is enough for a country with one of the youngest and fastest-growing populations in the region.

The UN World Economic Situation and Prospects 2025: Mid-Year Update, offers just a single passing mention of Pakistan by name. It lumps the country in with other IMF-dependent economies like Bangladesh and Sri Lanka, saying that all three are “expected to continue fiscal consolidation” and economic reforms under IMF guidance. That is hardly an endorsement.

When talking about South Asia as a whole, the document projects the region to grow by just over 5 percent. The 22-page report warns that short-term stability can hide structural weaknesses, especially in developing countries. It also highlights the global risks that could adversely affect Pakistan’s economic growth in the next few months, including slowing trade, fragile investment flows, climate-related disruptions, and an increasingly fragmented global order.

Considering the fact that Pakistan has a bulk youth population, a growth rate of 2.6 percent, or even double that rate, is barely enough to absorb new entrants into the job market

The IMF data scientists have been slightly more generous, and have credited Pakistan with improved fiscal discipline, declining inflation, and a shrinking current account deficit. The central bank has its own numbers to show and projects growth between 2.5 percent and 3.5 percent, and average inflation somewhere between 5.5 percent and 7.5 percent for the fiscal year.

All these data-driven reports acknowledge the fact that macroeconomic repair work is underway in the country amid challenges. Considering the fact that Pakistan has a bulk youth population, a growth rate of 2.6 percent, or even double that rate, is barely enough to absorb new entrants into the job market.

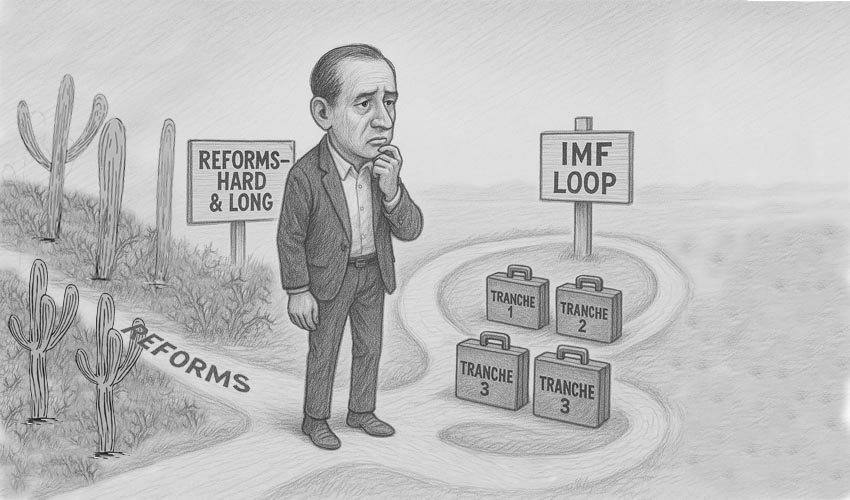

These reports have also issued warnings, and ignoring them is likely to land the country back at the IMF door. Instead of banking on loan tranches and remittances, the state must expand the tax base by bringing powerful and untaxed sectors like retail, real estate, and agriculture into the fold.

At the same time, tax administration must be enhanced to ensure that the burden of taxation is equitably distributed. Likewise, inefficiencies in the energy sector must be removed so that they do not continue to drain public finances and stall industrial growth. Pakistan has bought time, but it cannot afford to waste it. Policymakers must end their obsession with debt targets and realize that painful reforms are the only way to ensure real economic recovery.