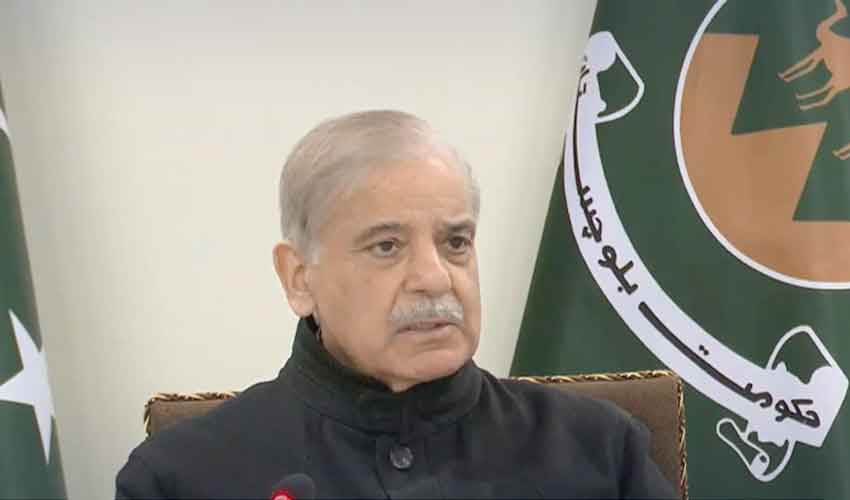

Pakistan cannot afford to be in survival mode anymore. The numbers Finance Minister Muhammad Aurangzeb shared while unveiling the Pakistan Economic Survey 2024-25 are promising, but there are also some concerning aspects. Inflation is down to a 60-year low, the current account is in surplus, and the government boasts a historic primary surplus of 3.0% of GDP in the first three quarters of the current fiscal year. However, while the pre-budget document is full of data, the only thing hard to find is a clear direction, something that is worrying and not to be celebrated.

While many believe the numbers make sense, they do not. The headline indicators highlighted in the economic survey offer some respite. Real GDP growth stands at 2.68%, which signals a reversal from previous contractions. Inflation also plummets to 0.3% in April 2025 compared to 17.3% a year ago. Moreover, the average inflation for July-April stands at 4.7% compared to last year’s 26%. However, these statistics represent an economy that has been forcibly shut down and starved into stability. The fiscal surplus came from frozen development, slashed imports, over-taxed essentials, and windfall revenues from the State Bank, not from any reform. The overly mentioned ‘financial discipline’ is just austerity, but under another name.

The document talks about falling inflation, but fails to mention how demand has collapsed with it. The 0.3% CPI in April has no mention of reduced incomes and food inflation remaining high in most working-class localities. The average Pakistani has simply stopped buying because they are unaffordable even when prices fall.

Fiscal restraint must now give way to structural reforms, not just in taxation or energy but also in investment policy. It is high time for Pakistan to reduce its dependence on external inflows, especially when it comes to remittances, which cannot remain a permanent substitute for productivity

Similarly, the survey mentions agriculture growing by a mere 0.56%. However, it also talks about major crops declining by double digits. Cotton production is down 30%, while wheat fell 8.9% mainly due to a marginal return on investment. Moreover, industry has barely moved, with large-scale manufacturing shrinking and FDI dropping. The current account surplus exists only because Pakistanis abroad kept sending dollars. Despite a surplus on paper, public debt has soared to Rs76 trillion, with external debt alone standing at $87 billion. A 2.68% growth rate means nothing when 38% of children are still out of school, with the percentage as high as 69% in Balochistan.

The Pakistan Economic Survey is honest in numbers but dishonest in spirit. It gives accounts of short-term indicators offering relief, but the government must not mistake economic stability for development. Fiscal restraint must now give way to structural reforms, not just in taxation or energy but also in investment policy. It is high time for Pakistan to reduce its dependence on external inflows, especially when it comes to remittances, which cannot remain a permanent substitute for productivity. It is now up to the government to either use the time it has bought to pursue meaningful reforms that can rebuild economic momentum, or be trapped in the illusion of economic growth.